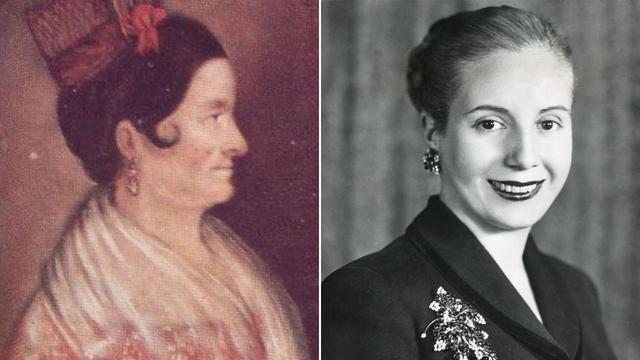

The Eva Perón of Silgo XIX?

In 1971, after a horrible journey of fifteen years that could well be considered as an absolute compendium of human evil, the corpse of Eva Perón presented undoubted signs of hatred, dislike and revenge. Several stab wounds to her temple and four to her forehead; a large gash on her cheek and arm; completely sunken nose; sectioned neck; nasal septum fracture; a finger of the hand (right) severed; fractured kneecaps; chest stabbed in four places; tar coating on the soles of her feet; perforated coffin lid; body coated with quicklime; and moldy, corroded shroud. The body of María Encarnación Ezcurra, on the contrary, survived immaculate. María Sáenz Quesada recalls that, when her body was transferred to the vault of the Ortiz de Rosas family in the Recoleta cemetery, eighty years after her death, it appeared “incorrupt”.

The source taken by the historian is that of a direct witness: Monsignor Marcos Ezcurra, Encarnación's great-nephew. “Her face could be portrayed with perfect features, with a yellowish wax white; bright brown hair falling in two wavy bands from a high, broad forehead; eyes closed but with a lively expression; her mouth half-open reciting a prayer and her dresses intact, the white habit of the Dominicans, around her neck the scapular of the Brotherhood of Sorrows, white wool stockings and brand-new black shoes […] she seemed asleep”. The cleric will then become mystical and say that this state of purity was caused by a "divine design", but it is not the idea here to delve into that cable car linked to the order of the mysterious.

It is simply a matter of using the state of both bodies postmortem to point out one of the few differences, beyond the contextual ones, that can be traced between two women of the three most important in Argentine history. Between Eva, poor and beautiful Eva, whom those wretches tried to remind her of her poor and "adulterous" origin until after she died, not knowing that the soul of the people would be with her forever. And also poor Encarnación, whose inert body was saved only because she was of ancestry. For coming from a good family, despite its popular, national and mazorquero turn. To compare “academically” the life and work of these two women born and lived in such a different historical context is a complex edge that we do not intend to transgress, of course. But trying, at another level of analysis, to thread ties of meaning that correspond to a current historical-political line in the national and popular imaginary: the one that her two husbands make up together with José de San Martín. Indeed, just like that of their colleagues, friends and husbands, the lives of Encarnación and Eva, even with the anachronisms saved, have more similarities than contrasts.

The most significant among the latter is marked by the aforementioned course of their bodies, a situation sealed by fire due to such dissimilar origins. Encarnación's lineage clearly differs from Evita's starting poverty. Juana Ibarguren, her mother, had given birth to her in La Unión, a rural area some twenty kilometers from Luján, in front of the cacique Coliqueo's toldería and helped by Juana Rawson de Guayaquil, a Mapuche midwife from the area. Very far from the cradle of ralea that fell to Encarnación, Eva left for life with a civil blemish stamped on the document ("adulterine daughter") and knew the privations from the breast of a mother who had to sew clothes for outside, with in order to guarantee the minimum sustenance for her and her five siblings. Nobody told Evita what poverty was.

The start of both, then, goes by itself. Shoot down any stupidity that is said about meritocracy. Eva, deprived of the slightest luxuries, in charge of stopping the pot at home and unable to get an education according to a girl her age. Encarnación, super cared for at home as a good girl, and educated as such, based on tutors and proper nutrition. Eva, who gets on the first train to Buenos Aires in order to escape the ordeal of the material and moral suffering caused by her condition as her natural daughter. Encarnación, who goes from her urban house to her parents' ranches during the summers, and she returns during the winters, lacking absolutely nothing material.

First and primal distance, then. Second distance: the position assumed by both, already grown-ups, with respect to the charity, also known as "Charity Ladies". Although –axial– those patrician ladies of the first half of the 19th century had not yet acquired the class splendor, of alms and contempt, that Eva would denounce until achieving her elimination in 1947. Encarnación was far from something like that. There are no direct testimonies of hers about the institution created by Martín Rodríguez, at the request of his government minister Bernardino Rivadavia, in 1823. It is confirmed that her husband Rosas minimized the margin of action of the institution in his second government. "During the Rosas government, the institution was reduced to its minimum expression." Among other measures tending to this, the economic difficulties caused by the French blockade in 1838 led the Restorer to suppress his subsidy.

Lade Beneficencia was a state organization designed to help and "educate" poor girls, a function that until then had been fulfilled by the Catholic Church, through various institutions such as the House of Spiritual Exercises or the Brotherhood of Charity. The political and educational management of the entity was carried out by women from high society and that is how it went, with its twists and turns, until Eva's decision to replace it with the Foundation, considering it an organization of "oligarchic philanthropy". Encarnación must have been far from it, especially if one takes into account that several women close to her, beyond Rosas's intervention, had a direct relationship with the , as in the case of Agustina Rosas, its president during that period, and the same Mariquita Sánchez, who would also reach that position.

In any case, the analogies between the two clearly prevail. The situation of the poor, beyond his possible opinion about the ladies, was not something that was strange, hostile or distant to Encarnación. It goes without saying because of what was worked on in previous chapters, that the Heroine of the Federation transformed into direct political actors the same sectors marginalized by the elites that Eva, a hundred years later, would call her "Descamisados" hers. Moreover, it can be inferred that the commitment of Rosas's wife is worth double because there had to be a colossal effort on her part to integrate culturally, socially and affectively into such sectors, being able to enjoy the honeys of wealth, as in fact her friend did. Ladybug. Nobody had to tell Eva about poverty. She had experienced it first hand. To Encarnacion, yes. Therefore, embracing the cause of those people from the outskirts of the city doubles her merits as a fighting woman, even beyond the limits that Rosas could set for her.

An empirical raid through both intense, fleeting lives, totally dedicated to the causes of her friends and colleagues, yields more synonyms than distances. It ratifies that, except for some details, both women have been similar. And a lot. In the same way that Encarnación, with her sights set on social justice –as it was understood in her time, of course–, never made any humble, dispossessed being from the low town, who met in her house, Eva saved or improved lives everywhere from the Foundation that replaced the Charity. “Alms humiliates and social help stimulates. Alms should not be organized, help should. Alms should disappear as the foundation of social assistance”, said the “Spiritual Chief of the Nation”.

In the same way that, with and through Encarnación, such sectors enjoyed a protection and consideration that they hardly received from the Levite aristocracy, or even from the schismatic federals, with the insistent work of Eva they were integrated into a society that he had almost always turned his back. “Eva […] traveled the length and breadth of the country, inciting the disinherited to join us […] I saw in Evita an exceptional woman. A true passionate, animated by a will and a faith that could be compared to that of the first Christians”, Perón will say about her “dear sweetie”, also inserting the Christian and popular wedge that also unifies the two protagonists.

The tremendous devotion of both for their husbands is another factor that unites them. That fanaticism of Encarnación, which led her to organize the Mazorca to watch Juan Manuel's back and even "take up arms" to force his return from the expedition to the South, is very similar to what Eva proposed when she tried to arm the CGT, in order to defend his Juan Domingo after the 1951 coup attempt orchestrated by Benjamín Menéndez. In fact, she Eva bought 5,000 automatic pistols and 1,500 machine guns from Holland for that purpose.

The Marquis of Payssac, from his position as French Consul in Buenos Aires, described Encarnación as a "courageous and small" woman, willing to give her life for her country, if the circumstances warranted it. . “Madame Rosas carries a pair of pistols at her waist as well as a dagger, because I am convinced that I would not be wrong if I say that if her husband or the country were in danger, this woman would be capable of the greatest dedication and the greatest efforts that only courage can inspire.”

Eva's courage for Perón is beyond doubt. There are phrases that could become an act at any time. "I served as a shield, my General, so that the attacks instead of going to you went to me". Or this other, more bawdy one, given after the recent coup attempt in 1951: “Be alert that the enemy is lurking [...] I ask God not to allow those foolish people to raise their hands against Perón because, wow! of that day! That day, my General, I will go out with the working people, I will go out with the women of the people, I will go out with the shirtless of the country so as not to leave standing any brick that is not Peronist [...] against the traitors from within and from outside, that in the dark of the night they want to leave the poison of their vipers in the soul and body of Perón, which is the soul and body of the country”.

Both women were loyal, passionate, impulsive, faithful and fanatical of their men, to the point of giving their lives for them. Or was not that uterine cancer that devoured Eva the visible, tangible result of her tireless struggle for the liberated homeland, and for Perón, who is not the same, but is the same? Or was it not the paralysis that killed Encarnación, the cause of the invasive, treacherous and alienating blows that Rosas received as soon as she assumed her second term, or of that loneliness that she had to go through during various stretches of her life, especially that of the critical period 1832-1835, due to the absence of your man?

The indomitable, brave and brave character of both women cannot be avoided when it comes to drawing synonyms between the fights with her loved ones. It is enough to recite one of Encarnación's letters to Rosas, to associate directly with the Eva that was giving Perón a handstand, and her pimps on duty. “The masses are more willing every day, and they would be better off if your circle wasn't so screwed up, because there are those who are more afraid than ashamed. But I confront them all and I fight the same with the schismatics as with the weak apostolics, because the ones I like are the ones with the ax and the chuza”.

The “fucked up” that Encarnación refers to are none other than the “tycoons” who exploit Juan Manuel. That triumphalist "type" and contrary to the "axe and chuza", the seasoned militants of the federal cause that the heroine intends to help. "They who have no aspirations continue to support you, they enter and leave our house, where you know, they never lack a plate of food," she will write. Another forceful letter, also already mentioned, is the one that confesses to Vicente González, the Carancho del Monte, that if Juan Manuel was careless with her “I will have to make a revolution to him”. The intention is not far from what Eva surely had when she affirmed that the enemies worked in the shadow of treason, the traitors "inside" who, between being and not being of the homeland, opted for the second, just like the from outside. Fear also unites them. Or the way they were called by the liberal opponents, the “progressive” sectors, the aristocratic. Encarnación, given her closeness to the black men and women of the city, was even called “the mulatto Toribia”, or accused of being licentious and “chupandina”, as has been seen in previous chapters of her. In the same way, similar social groups tried to denigrate Evita with nicknames such as "la perona", "maintained lover", "bastard". A hatred entrenched in the imaginary of the middling that Encarnación finally got rid of, but Eva did not. No one would forgive her that, among so many acts in favor of the homeland and the humble, she told Perón one of the most beautiful and genuine phrases of her life: “Never abandon the poor. They are the only ones who know how to be faithful.”

The black book of the Second Tyranny, published in 1958, has no waste in this regard. “The dictator […] had by his side from the beginning of his public life, a strange woman different from almost all Creoles. She was uneducated, but not politically savvy; she was vehement, domineering and spectacular. She received ideas, but she put passion and courage. The dictator simulated many things, she almost none. She was an indomitable, aggressive, spontaneous, perhaps tomboyish little beast [sic]. Her nature had endowed her with pleasing physical features, which she accentuated when her propitious fortune allowed her to wear jewels and splendid dresses. […] The dictator let 'the lady' do it. He knew that his outbursts convinced the primary people more than his own indoctrination speeches […] his early death spared the country further disturbances”.

Of course, the popular brilliance, the validity of Eva Perón, loved by the poor and dispossessed not only from here but from all over the world, far exceeds the trails of Ezcurra, almost submerged in the mists of time. A thousand reasons explain it, of course, but little by little the figure of the latter is taking on a historical transcendence at the height of the circumstances. Lorena Escofet, director and author of the play Yo, Encarnación, is one of those trying to rescue her and defend her from a gender perspective. “Perhaps in the times in which we live193 and with the importance that the movement took on in these years, it could be (a work) more than interesting for feminism. It is evident that what this one proposes has a look that comes from a woman and on a female character, something that is never in doubt”.

Among several, the work deals with another possible analogy between the two women: the recurrent, although debatable idea, that at the peak of power her men have not embraced them. Or at least not enough. “They did not have the place of their own that they deserved. His companions could not avoid the model that the patriarchy imposed on them. They could not escape their historical context. Surely the rest of the protagonists of the power of their moment would not have allowed them either. So, only premature death remained. The silence". Two phrases from her respective husbands offer plafond to the plate. Perón will say about Eva: "Her guts could generate uncontrolled attitudes and irremediable consequences." "You no longer have anything to do now, you were already useful to me, I love you and I want to see you healthy and strong", she would say for Rosas about Encarnación, after having returned to power in 1835.

To counteract such a probable "failure" counts the courage that both popular leaders had to face the morality of their respective times. Rosas, as was seen, defended her wife to the point of confronting her brave mother for her. Perón did the same with Eva, when they treated her like a prostitute and a whore. It was because they feared him, just like Encarnación. “[…] As my name has sounded decisively against the furious, [Viamonte] is afraid of me, and because he must be sure [that] I will not shut up when he does not behave well, that is, when he causes misfortune to my homeland, and of good men”, Encarnación wrote. “We are never going to allow ourselves to be exploited by the oligarchic and treacherous boot of the traitorous traitors who have exploited the working class,” Eva will shout, provoking gorillas and soldiers from the non-patriotic wing to sting. “I want the people to know that we are willing to die for Perón […] and for the traitors to know that we will no longer come here [Plaza de Mayo] to say present! To Perón […] but we will go to do justice with our own hands”.

The positive comparison between both women will also arise from historians such as Lucía Gálvez, Vera Pichel, María Sáenz Quesada or Pacho O'Donnell, among others. There will also be negative ones, as in the case of Américo Ghioldi who, for the purpose of comparing the first and second tyranny, which the socialist leader attributed to the Rosas-Perón line, equaled his two women.

Lastly, the social effect of the deaths of Eva and Encarnación also counts in the column of possible synonyms. On average, taking into account the number of inhabitants in the province in 1838, the year of Encarnación's death, and in 1952, the year of Eva's death, popular attendance at funerals was quite equivalent. Two million of the more than four who inhabited the province watched over Eva, and 25,000 were those who attended the one in Encarnación, in an urban population of sixty thousand people. A strong flat in this regard is that, while the recently deceased body of the heroine of the Federation was transferred to the San Francisco de Monserrat convent, that of Eva first went to the Ministry of Labor, and then went to the CGT. Hence, perhaps, the terrifying evolution of her body, that of the most feared death, when the true Nazis of Argentine history staged the coup in September 1955.

KEEP READING

Encarnación Ezcurra: the incredible life of a woman who was mocked by everyone and became the great love of Juan Manuel de Rosas Encarnación Ezcurra: the woman who gave everything for Rosas and his role in the first death in a political escrache